Das E-Learning-Projekt „Musik im KZ Theresienstadt“ soll Schülerinnen und Schülern Grundlagenwissen über das Lager vermitteln.

Das E-Learning-Projekt „Musik im KZ Theresienstadt“ soll Schülerinnen und Schülern Grundlagenwissen über das Lager vermitteln. (The e-learning project "Music in Theresienstadt Concentration Camp" aims to provide pupils with basic knowledge about the camp. )

Deutsch

Erinnern durch E-Learning

Mit virtuellen Zeitzeugnissen konservieren LMU-Forschende die Erinnerung an das Grauen des Nationalsozialismus. Im E-Learning-Projekt „Musik im KZ Theresienstadt“ werden Interviews mit Überlebenden für Schülerinnen und Schüler aufbereitet, bei „Voices from Ravensbrück“ für Forschende.

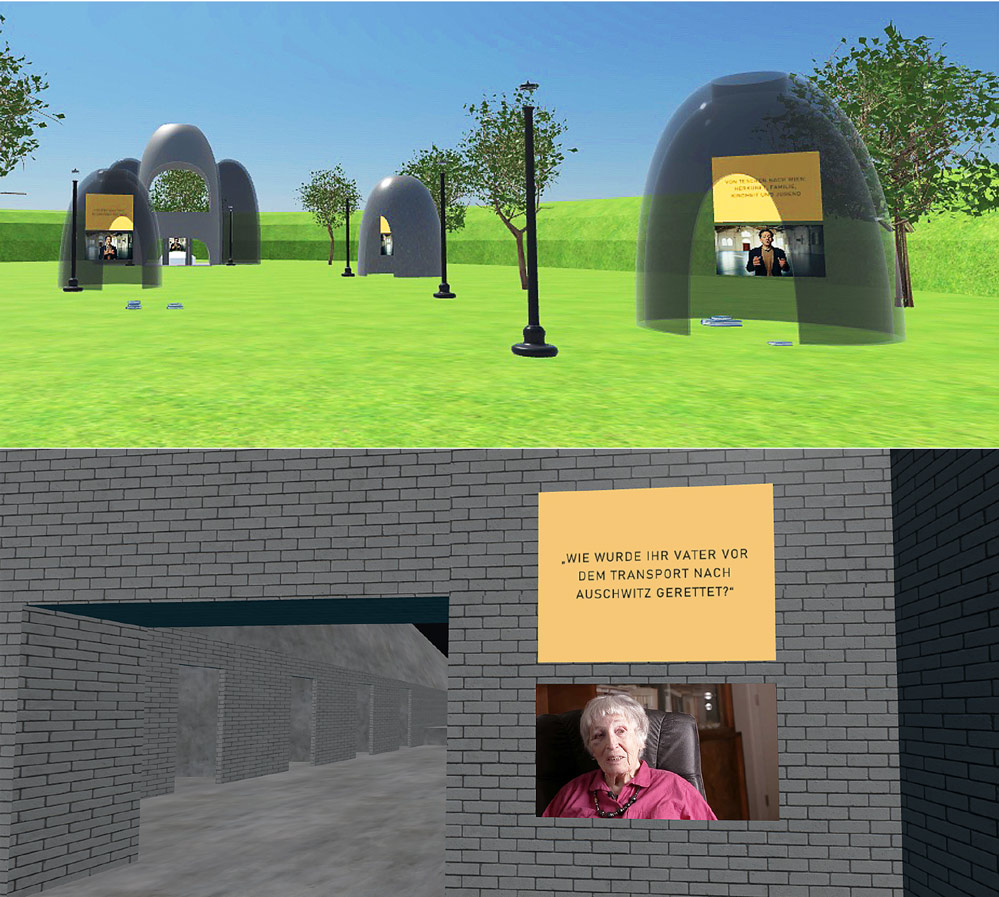

Mit ein paar Klicks gelangt man in das virtuelle Konzentrationslager Theresienstadt. Dort trifft man die Überlebende Dr. Michaela Vidláková, sieht Ausschnitte eines Propagandafilms der Nazis, hört aber auch die wunderbare Musik, die seinerzeit in Theresienstadt komponiert wurde. Das E-Learning-Projekt „Musik im KZ Theresienstadt“ des Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich soll Schülerinnen und Schülern Grundlagenwissen über das Lager vermitteln – und über Kunst und Kultur, die dort entstanden sind.

Die Idee dazu hatte Daniel Grossmann, Gründer und Dirigent des Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich. „Dass im KZ Theresienstadt ein umfangreiches kulturelles Leben stattfand und sogar zahlreiche Werke dort komponiert und uraufgeführt wurden, ist wenig bekannt“, erklärt er. „Als Dirigent bedeutet es mir sehr viel, der Erinnerung an diese Künstlerinnen und Künstler gerecht zu werden.“

Entwickelt wurde die Plattform in Kooperation mit der LMU und der Technischen Universität München (TUM). „Schon länger beschäftigen wir uns mit digitalen Tools zur Holocaust Education“, erklärt Germanist Ernst Hüttl, der das Projekt als Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Lehrstuhl für Deutschdidaktik auf LMU-Seite betreute. „Im Projektverbund LediZ beispielsweise wurden unterschiedliche interaktive Zeitzeugnisse entwickelt.“ So können 3D-Projektionen von Holocaust-Überlebenden mithilfe von Sprachverarbeitung auf Fragen antworten. Und „Abba‘s Hub“ stellt die Lebensgeschichte des litauischen Holocaust-Überlebenden Abba Naor als begehbare Zeitleiste mit 3D-Umgebung dar.

„Die Weise von Liebe und Tod“ in 360 Grad

Die neue Plattform „Musik im KZ Theresienstadt“, in die man sich mit VR-Brille, aber auch am Smartphone oder Computer begeben kann, sei ein „sehr kompaktes Lernpaket“, so Hüttl. Darin geht es auch um die ambivalente Seite der Musik in Theresienstadt – als Propagandamittel für die Täter, aber auch als Überlebenswerkzeug für die Inhaftierten. Im Fokus standen Leben und Werk Viktor Ullmanns, eines Komponisten, der im KZ Theresienstadt komponierte, bevor er in Auschwitz ermordet wurde.

Drei virtuelle Räume, entwickelt von Studierenden der Architekturinformatik der TUM, repräsentieren die Lebensgeschichte Ullmanns. Hüttl selbst bereitete sie technisch auf und befüllte sie mit Medien: historischen Fotos, Quellentexten, Audiobeispielen und Interviews.

Mithilfe dieser Medien beantworten die Schülerinnen und Schüler Fragen und erhalten bei richtiger Antwort Zugang zum nächsten Raum. Am Ende des Quiz gelangen sie zu einem 360-Grad-Video einer Aufführung des Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich in Theresienstadt. Dirigent Grossmann hatte das KZ dafür mit seinen Musikern besucht und sie räumlich getrennt positioniert – im Waschzimmer, Schlafräumen oder dem Theatersaal. So wurde die letzte Komposition Viktor Ullmanns „Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke“ aufgeführt – eine visuell wie akustisch eindrucksvolle Aufzeichnung.

Transkription mit Künstlicher Intelligenz

Aus anderer Perspektive befasst sich Dr. Christoph Draxler vom Institut für Phonetik und Sprachverarbeitung der LMU mit Holocaust-Zeugnissen. In dem Projekt „Voices from Ravensbrück: The Value of Multilingual Oral History” bereitete er mit Kolleginnen und Kollegen aus Italien und den Niederlanden Zeitzeuginnen-Interviews für die Forschung auf. „Das KZ Ravensbrück bei Berlin war als reines Frauenlager mit Inhaftierten aus über 30 Ländern ein sehr spezielles, multilinguales Lager“, erklärt der Informatiker und romanistische Linguist, der sich seit Langem mit Webtools für phonetische Forschung, Abfragemethoden in Sprachdatenbanken sowie Dialektologie befasst.

Ausgangspunkt des Projekts waren Interviews mit Überlebenden des KZ, die in den 70er-Jahren in Italien aufgenommen worden waren. Das Forschenden-Team digitalisierte die Tonbandaufnahmen, sammelte weitere Interviews aus verschiedenen Ländern der Welt und bereitete sie für die Forschung auf.

Draxlers Part war dabei die Verschriftlichung. „Die Wortfehlerrate heutiger Transkriptions-Programme ist dank Künstlicher Intelligenz sehr vielbesser geworden“, so Draxler. „Was KI noch nicht kann – die wissenschaftliche Transkription aber leisten muss –, ist das Erkennen von Häsitationen, Wiederholungen oder Satzabbrüchen. Denn diese Phänomene sind für das Verständnis der Gesprächssituation entscheidend.“ Bei der Transkription der Zeitzeugen-Interviews müsse das Programm zudem mit berücksichtigen, dass bei den sehr persönlichen Geschichten keine Persönlichkeitsrechte des Interviewpartners oder Dritter verletzt würden.

Mehr als abstrakte Zahlen

Zusammengeführt wurden die Interviews und Transkripte auf CLARIN, der europäischen Plattform für Sprachforschungsdaten. In einem neuen „Oral History“-Bereich, der auf der Arbeit von Draxler und seinen Projekt-Partnerinnen und -Partnern basiert, können Forschende nun entsprechende Zeitzeugnisse erfassen und auffinden sowie über Sprachdaten, die es in Archiven weltweit zu Ravensbrück gibt, recherchieren. Damit auch Forschende ohne IT-Kenntnisse Transkriptions-Software für Zeitzeugengespräche nutzen können, testete man im Rahmen des Ravensbrück-Projekts ein selbst entwickeltes, „radikal einfach zu bedienendes“ Programm – bei gleicher Fehlerrate, als würde man es selbst abtippen.

Zusammengeführt wurden die Interviews und Transkripte auf CLARIN, der europäischen Plattform für Sprachforschungsdaten. In einem neuen „Oral History“-Bereich, der auf der Arbeit von Draxler und seinen Projekt-Partnerinnen und -Partnern basiert, können Forschende nun entsprechende Zeitzeugnisse erfassen und auffinden sowie über Sprachdaten, die es in Archiven weltweit zu Ravensbrück gibt, recherchieren. Damit auch Forschende ohne IT-Kenntnisse Transkriptions-Software für Zeitzeugengespräche nutzen können, testete man im Rahmen des Ravensbrück-Projekts ein selbst entwickeltes, „radikal einfach zu bedienendes“ Programm – bei gleicher Fehlerrate, als würde man es selbst abtippen.

„Allein über das Unterrichten abstrakter Zahlen kann man die Tragödie des Holocaust nicht vermitteln“, erklärt Dirigent Daniel Grossmann. „Aus einer jüdischen Familie stammend, die in weiten Teilen vernichtet wurde, ist mir die Erinnerung an einzelne Opfer des Holocaust sehr wichtig.“

English

Remembering through e-learning

LMU researchers are preserving the memory of the horrors of National Socialism with virtual testimonies. In the e-learning project "Music in Theresienstadt Concentration Camp", interviews with survivors are prepared for schoolchildren, and in "Voices from Ravensbrück" for researchers.

With a few clicks you can enter the virtual concentration camp Theresienstadt. There you meet the survivor Dr. Michaela Vidláková, see excerpts of a Nazi propaganda film, but also hear the wonderful music that was composed in Theresienstadt at the time. The e-learning project "Music in Theresienstadt Concentration Camp" by the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich aims to provide pupils with basic knowledge about the camp - and about the art and culture that was created there.

The idea came from Daniel Grossmann, founder and conductor of the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich. "The fact that there was an extensive cultural life in the Theresienstadt concentration camp and that numerous works were even composed and premiered there is little known," he explains. "As a conductor, it means a lot to me to do justice to the memory of these artists."

The platform was developed in cooperation with the LMU and the Technical University of Munich (TUM). "We have been working on digital tools for Holocaust education for a long time," explains German scholar Ernst Hüttl, who supervised the project as a research assistant at the Chair of German Didactics at LMU. "In the LediZ project network, for example, different interactive contemporary testimonies were developed." For example, 3D projections of Holocaust survivors can answer questions with the help of speech processing. And "Abba's Hub" presents the life story of Lithuanian Holocaust survivor Abba Naor as a walk-through timeline with a 3D environment.

"The way of love and death" in 360 degrees

The new platform "Music in Theresienstadt Concentration Camp", which you can enter with VR glasses, but also on your smartphone or computer, is a "very compact learning package", says Hüttl. It also deals with the ambivalent side of music in Theresienstadt - as a propaganda tool for the perpetrators, but also as a survival tool for the prisoners. The focus was on the life and work of Viktor Ullmann, a composer who composed in the Theresienstadt concentration camp before being murdered in Auschwitz.

Three virtual rooms, developed by students of architectural informatics at TUM, represent the life story of Ullmann. Hüttl himself prepared them technically and filled them with media: historical photos, source texts, audio examples and interviews.

With the help of these media, the pupils answer questions and, if they answer correctly, are given access to the next room. At the end of the quiz, they are taken to a 360-degree video of a performance by the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich in Theresienstadt. Conductor Grossmann had visited the concentration camp with his musicians for this and positioned them spatially separately - in the washroom, bedrooms or the theatre hall. This is how Viktor Ullmann's last composition "Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke" was performed - a visually and acoustically impressive recording.

Transcription with Artificial Intelligence

From a different perspective, Dr Christoph Draxler from the Institute of Phonetics and Speech Processing at LMU is dealing with Holocaust testimonies. In the project "Voices from Ravensbrück: The Value of Multilingual Oral History", he and colleagues from Italy and the Netherlands prepared eyewitness interviews for research. "As an all-women's camp with prisoners from over 30 countries, Ravensbrück concentration camp near Berlin was a very special, multilingual camp," explains the computer scientist and Romance linguist, who has been working for a long time on web tools for phonetic research, query methods in language databases and dialectology.

The starting point of the project were interviews with concentration camp survivors recorded in Italy in the 1970s. The research team digitised the tape recordings, collected further interviews from various countries around the world and prepared them for research.

Draxler's part was the transcription. "The word error rate of today's transcription programmes has become much better thanks to artificial intelligence," says Draxler. "What AI cannot yet do - but scientific transcription must do - is recognise haesitations, repetitions or sentence breaks. Because these phenomena are crucial for understanding the conversation situation." When transcribing the eyewitness interviews, the programme also has to take into account that the very personal stories do not violate the personal rights of the interviewee or third parties.

More than abstract numbers

The interviews and transcripts were brought together on CLARIN, the European platform for language research data. In a new "oral history" area based on the work of Draxler and his project partners, researchers can now record and find corresponding contemporary testimonies and research language data on Ravensbrück available in archives worldwide. To enable researchers without IT skills to use transcription software for eyewitness interviews, the Ravensbrück project tested a self-developed, "radically easy-to-use" programme - with the same error rate as if you were typing it yourself.

The interviews and transcripts were brought together on CLARIN, the European platform for language research data. In a new "oral history" area based on the work of Draxler and his project partners, researchers can now record and find corresponding contemporary testimonies and research language data on Ravensbrück available in archives worldwide. To enable researchers without IT skills to use transcription software for eyewitness interviews, the Ravensbrück project tested a self-developed, "radically easy-to-use" programme - with the same error rate as if you were typing it yourself.

"You can't convey the tragedy of the Holocaust just by teaching abstract numbers," explains conductor Daniel Grossmann. "Coming from a Jewish family that was largely annihilated, the memory of individual victims of the Holocaust is very important to me."

Italiano

Ricordare attraverso l'e-learning

I ricercatori della LMU conservano la memoria degli orrori del nazionalsocialismo con testimonianze virtuali. Nel progetto di e-learning "Musica nel campo di concentramento di Theresienstadt", vengono preparate interviste con i sopravvissuti per gli studenti e in "Voci da Ravensbrück" per i ricercatori.

Con pochi clic si può entrare nel campo di concentramento virtuale di Theresienstadt. Lì si incontra la sopravvissuta Dr. Michaela Vidláková, si vedono spezzoni di un film di propaganda nazista, ma si ascolta anche la meravigliosa musica composta all'epoca a Theresienstadt. Il progetto di e-learning "Musica nel campo di concentramento di Theresienstadt" dell'Orchestra da Camera Ebraica di Monaco di Baviera mira a fornire agli studenti le conoscenze di base sul campo - e sull'arte e la cultura che vi sono state create.

L'idea è di Daniel Grossmann, fondatore e direttore dell'Orchestra da Camera Ebraica di Monaco. "Il fatto che nel campo di concentramento di Theresienstadt ci fosse un'ampia vita culturale e che numerose opere siano state composte e presentate in prima assoluta è poco noto", spiega Grossmann. "Come direttore d'orchestra, significa molto per me rendere giustizia alla memoria di questi artisti".

La piattaforma è stata sviluppata in collaborazione con la LMU e l'Università Tecnica di Monaco (TUM). "Lavoriamo da tempo sugli strumenti digitali per l'educazione all'Olocausto", spiega lo studioso tedesco Ernst Hüttl, che ha supervisionato il progetto come assistente di ricerca presso la cattedra di didattica tedesca della LMU. "Nella rete del progetto LediZ, ad esempio, sono state sviluppate diverse testimonianze interattive contemporanee". Ad esempio, le proiezioni in 3D dei sopravvissuti all'Olocausto possono rispondere alle domande con l'aiuto dell'elaborazione vocale. E "Abba's Hub" presenta la storia della vita di Abba Naor, sopravvissuto all'Olocausto in Lituania, sotto forma di una linea del tempo percorribile con un ambiente 3D.

"La via dell'amore e della morte" a 360 gradi

La nuova piattaforma "Musica nel campo di concentramento di Theresienstadt", alla quale si può accedere con gli occhiali VR, ma anche con lo smartphone o il computer, è un "pacchetto didattico molto compatto", dice Hüttl. Si occupa anche del lato ambivalente della musica a Theresienstadt: come strumento di propaganda per i carnefici, ma anche come strumento di sopravvivenza per i prigionieri. L'attenzione si è concentrata sulla vita e sul lavoro di Viktor Ullmann, un compositore che compose nel campo di concentramento di Theresienstadt prima di essere ucciso ad Auschwitz.

Tre stanze virtuali, sviluppate dagli studenti di informatica architettonica del TUM, rappresentano la storia della vita di Ullmann. Hüttl stesso le ha preparate tecnicamente e le ha riempite di media: foto storiche, testi originali, esempi audio e interviste.

Con l'aiuto di questi supporti, gli alunni rispondono alle domande e, se rispondono correttamente, hanno accesso alla stanza successiva. Alla fine del quiz, vengono portati in un video a 360 gradi di un'esibizione dell'Orchestra da Camera Ebraica di Monaco a Theresienstadt. Il direttore d'orchestra Grossmann ha visitato il campo di concentramento con i suoi musicisti e li ha posizionati spazialmente in modo separato: nei bagni, nelle camere da letto o nella sala del teatro. È così che è stata eseguita l'ultima composizione di Viktor Ullmann "Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke": una registrazione di grande impatto visivo e acustico.

Trascrizione con intelligenza artificiale

Da una prospettiva diversa, il dottor Christoph Draxler dell'Istituto di fonetica ed elaborazione del parlato della LMU si occupa di testimonianze dell'Olocausto. Nel progetto "Voices from Ravensbrück: The Value of Multilingual Oral History" (Voci da Ravensbrück: il valore della storia orale multilingue), insieme a colleghi italiani e olandesi ha preparato interviste a testimoni oculari per la ricerca. "Il campo di concentramento di Ravensbrück, vicino a Berlino, era un campo di concentramento multilingue molto particolare, in quanto era un campo di sole donne con prigionieri provenienti da oltre 30 Paesi", spiega l'informatico e linguista romanista, che da tempo si occupa di strumenti web per la ricerca fonetica, di metodi di interrogazione nei database linguistici e di dialettologia.

Il punto di partenza del progetto sono state le interviste ai sopravvissuti dei campi di concentramento registrate in Italia negli anni Settanta. Il team di ricerca ha digitalizzato le registrazioni su nastro, ha raccolto altre interviste in vari Paesi del mondo e le ha preparate per la ricerca.

Draxler si è occupato della trascrizione. "Il tasso di errore di parola degli attuali programmi di trascrizione è migliorato molto grazie all'intelligenza artificiale", afferma Draxler. "Quello che l'AI non può ancora fare - ma che la trascrizione scientifica deve fare - è riconoscere le esitazioni, le ripetizioni o le interruzioni di frase. Perché questi fenomeni sono fondamentali per comprendere la situazione della conversazione". Nel trascrivere le interviste ai testimoni oculari, il programma deve anche tenere conto del fatto che le storie molto personali non violano i diritti personali dell'intervistato o di terzi.

Più che numeri astratti

Le interviste e le trascrizioni sono state raccolte su CLARIN, la piattaforma europea per i dati della ricerca linguistica. In una nuova area di "storia orale" basata sul lavoro di Draxler e dei suoi partner di progetto, i ricercatori possono ora registrare e trovare le corrispondenti testimonianze contemporanee e i dati linguistici di ricerca su Ravensbrück disponibili negli archivi di tutto il mondo. Per consentire ai ricercatori che non dispongono di competenze informatiche di utilizzare un software di trascrizione per le interviste ai testimoni oculari, il progetto Ravensbrück ha testato un programma sviluppato in proprio, "radicalmente facile da usare" - con lo stesso tasso di errore che si avrebbe digitando da soli.

Le interviste e le trascrizioni sono state raccolte su CLARIN, la piattaforma europea per i dati della ricerca linguistica. In una nuova area di "storia orale" basata sul lavoro di Draxler e dei suoi partner di progetto, i ricercatori possono ora registrare e trovare le corrispondenti testimonianze contemporanee e i dati linguistici di ricerca su Ravensbrück disponibili negli archivi di tutto il mondo. Per consentire ai ricercatori che non dispongono di competenze informatiche di utilizzare un software di trascrizione per le interviste ai testimoni oculari, il progetto Ravensbrück ha testato un programma sviluppato in proprio, "radicalmente facile da usare" - con lo stesso tasso di errore che si avrebbe digitando da soli.

"Non si può trasmettere la tragedia dell'Olocausto solo insegnando numeri astratti", spiega il direttore d'orchestra Daniel Grossmann. "Provenendo da una famiglia ebraica che è stata in gran parte annientata, la memoria delle singole vittime dell'Olocausto è molto importante per me".

|

|

Ernst Hüttl Ernst Hüttl |

The original article (in German) can be found here.

The translations were automatically generated with DeepL